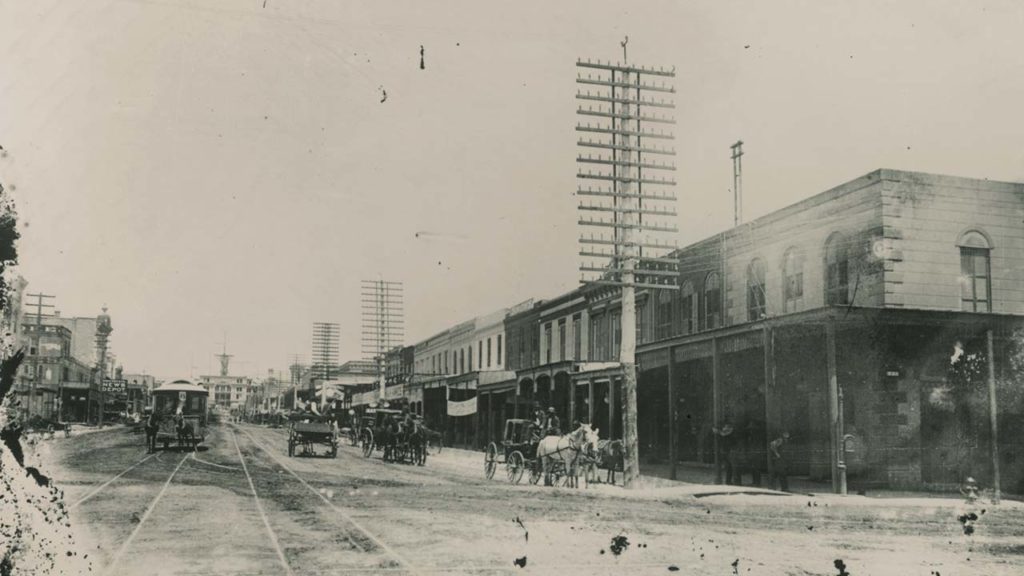

In the 1880s, Austin, Texas, was on the verge of becoming one of the most modern cities in the world. Business was booming. Railroads made ranching more profitable. Austin hadn’t been hit by Reconstruction like most of the South. The small city espoused the Victorian values of cleanliness, orderly behavior and familial values.

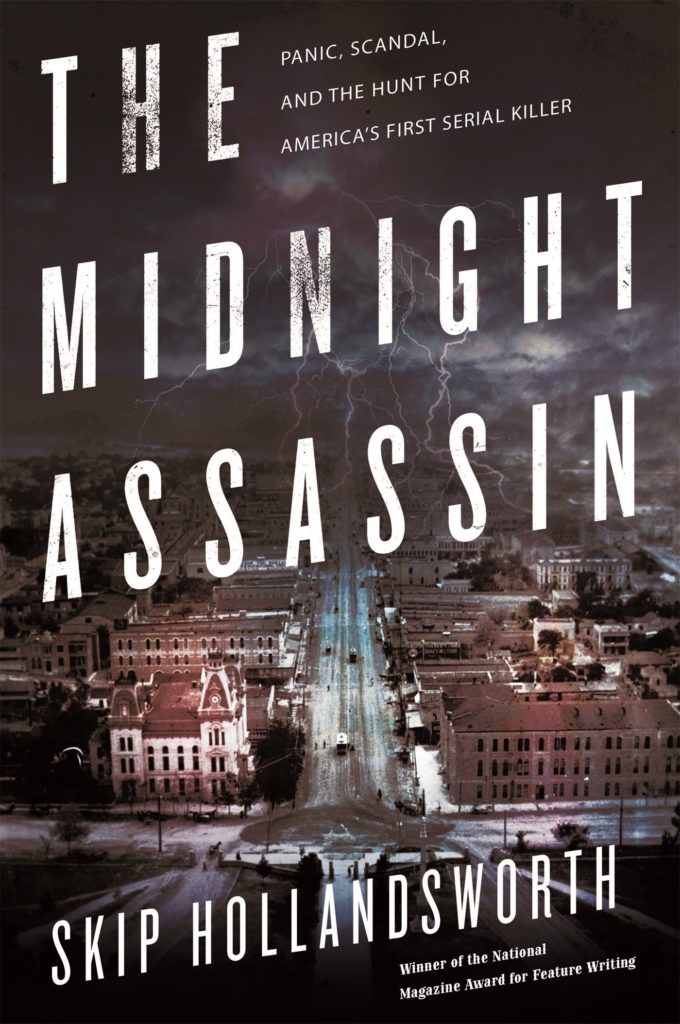

Then on New Year’s Eve 1884, a killer began a year-long reign of terror over the citizens of Austin. Before he (or she) was finished, there would be seven dead and several more wounded and disfigured. Then just as suddenly, the murders stopped.

With forensics in its infancy and Texan vigilantism still a way of life, an orderly investigation was essentially impossible. In the rush to help victims, allow bloodhounds to chase a scent or search the area for the criminal, evidence was trampled and ruined.

Hollandsworth couples the crime scene investigation with local politics, social distinctions, commerce and technology. The murderer began his spree with young servant women, all of whom were African-American. He attacked them at night, in their quarters which we often small shacks at the rear of the property. His weapon of choice was often an axe and in some cases and ice pick.

Though there was some outcry at the startling crimes, the fear would not reach a fever pitch until he began to target white, middle and upper class women.

And when the horrible stories began to make national news, the city leaders started to wonder what would happen to the investors at the door. After all, the largest state capitol building in America was being built just up the street.

Hollandsworth connects the crimes to the effects of electricity in the cities. Unable to apprehend the killer (or even find substantial evidence), the next best thing would be to deter him. Since he always struck in the depths of night, creeping in from a darkened alley, they decided to light the night. If he had no place to hide, he couldn’t murder.

Austin’s downtown was fitted with tall structures full of the newest lightbulbs. Businesses also installed lighting and their warm glow spilled out into the streets from their shop windows.

(Even after the murders ended, Austin installed “moonlight” towers throughout its neighborhoods. The structures have since been placed on the historic registry.)

Throughout the afternoon, customers lined up at Bill Johnson’s market to buy meats for their Christmas Eve dinners, the counters loaded with steaks, hams, turkeys, venison, and some of the last buffalo meat left in Texas. Others visited Prade’s ice-cream parlor, where clerks were selling Christmas fruit baskets, ornamented cakes, and French candy for twenty cents a pound. Men drove their wagons to Radam’s Horticultural Emporium to buy Yule trees to carry back to their homes for their children to decorate. One man pulled up in his wagon at H. H. Hazzard’s music shop to purchase a piano.

As the sun began to set, Henry Stamps, the city’s lamplighter, performed his usual role of lighting the gas lamps along Congress Avenue and Pecan Street, the city’s two main boulevards. The owners of the restaurants and saloons turned on their incandescent lights. …

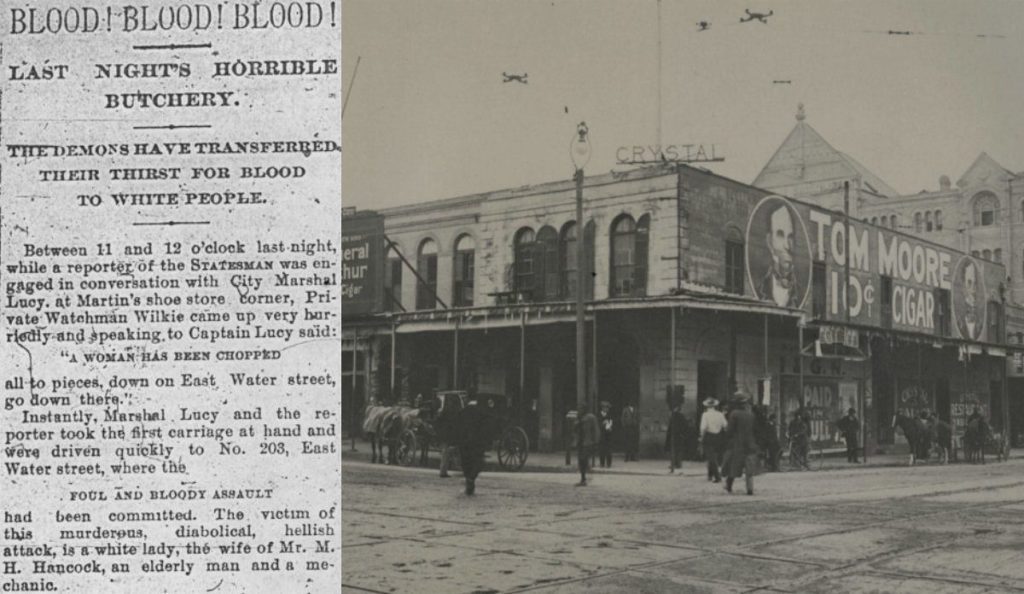

Suddenly, there were hoofbeats. A horse was seen coming straight up Congress Avenue from south of downtown, and it was coming fast, whipping through the cones of light thrown out by the gas lamps. On the back of the horse was a man named Alexander Wilkie, a night watchman at one of the saloons.

“A woman has been chopped to pieces!” Wilkie yelled. “It’s Mrs. Hancock! On Water Street!” …

To increase the amount of light, merchants came to their dark stores to turn on their incandescent lamps. Several women, tears streaming down their faces, huddled in carriages under the “outdoor lamp” that Charles Millett, the owner of Millett’s Opera House, had placed by his front doors so that potential patrons walking by at night could read his marquee about upcoming shows.

Finally, the sun rose. Throughout the city, church bells rang to signify the arrival of Christmas Day. But for all practical purposes, Christmas had been canceled in Austin—presents left unopened under the Christmas trees and dinners uncooked. ~Pgs 138-152

Read the full excerpt in Texas Monthly.

Hollandsworth gives context. The reader understands what Austin is, what Texas wants to be, and how bizarre and horrifying these murders are. Years of research went into the book, and not just criminal records. He tracks the lives of law enforcement, victim’s families, and business owners. Fans of Erik Larson will appreciate how Hollandsworth fills out the portrait rather than only recounting a bloody crime for sensationalism.

By 1888, the stories of Jack the Ripper covered the newspapers. Many believed it to be the work of the same killer. Hollandsworth sifts through these doubtful claims but it is clear not even he believes them. Perhaps it was only the hopefulness of a recovering city that there were not two such monsters in the world — and it was across the Atlantic Ocean.

My thanks to Henry Holt & Co. for the review copy.

___

Hardcover: 336 pages

Publisher: Henry Holt and Co.; First Edition edition (April 5, 2016)

Language: English

ISBN-10: 0805097686

ISBN-13: 978-0805097689

ASIN: 0805097678