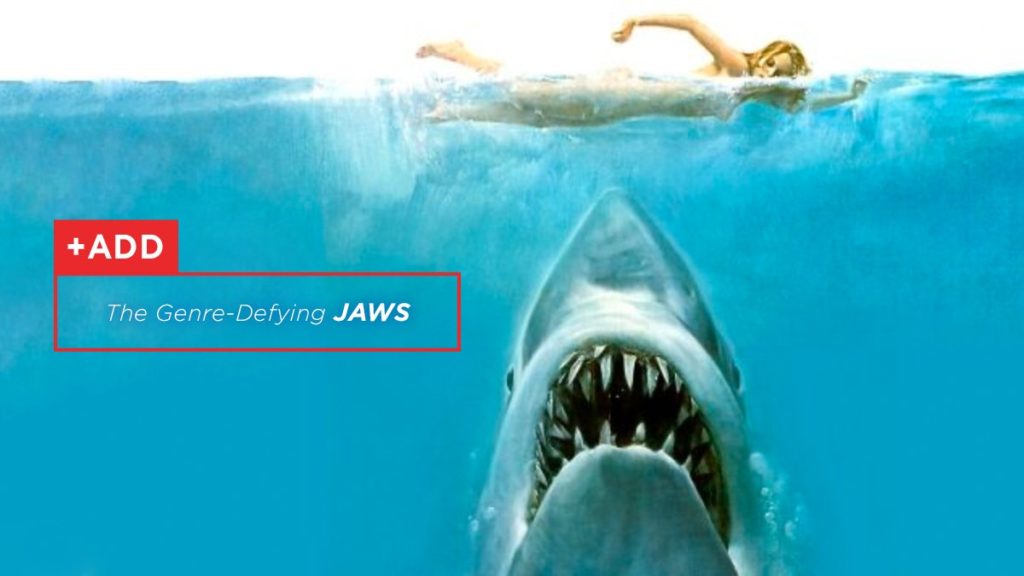

It’s easy to write Jaws off as a campy summer blockbuster. A murderous shark picking off beachgoers is a rather silly concept on its face. But when you add a grizzled misanthrope, a nerdy oceanographer, a troubled sheriff, and a single-minded monster, there is something more. Repeated viewings bring other, deeper meanings to the surface.

Like a typical slasher horror movie, Jaws opens with two teenagers sneaking out onto the beach dunes to go skinny dipping. Because of all the cues an audience has been trained to recognize, the viewer knows something bad is going to happen. Yet at the climax of the scene, instead of a piercing scream, there is silence. Only his second feature-length directing credit, Steven Spielberg was already learning to use the tropes of genres to his advantage.

Jaws is primarily a monster movie. It is a tale of man versus beast. But unlike its predecessors, Jaws employs an unusual creature. The audience feels for Frankenstein’s monster and the Gill Man. Godzilla’s fury is understandable, but this shark is a pure killing machine. It has “dead eyes” and has no purpose other than to destroy. Spielberg gives viewers a true villain to hate.

And like the best creature features, the viewer barely sees the shark. Though this was a deliberate choice, the physical shark was seen on screen even less due to the difficult mechanics it employed. Despite its detailed machinery, it proved nearly impossible to get footage that looked realistic. As a result the intrepid film editor inserted only short sequences of mechanical shark film.

In the end, it made a more frightening, subtler monster, and ironically, allows the film to stand the test of time more than one relying on computer graphics.

The classic American novel Moby Dick is at its center a story about obsession. Captain Ahab and the elusive white whale blur the line between predator and prey, each eschewing everything else in order to kill the other. More importantly, they insist on finishing what was left undone. Neither can rest while they know the other is still alive.

Quint, played by the rugged Robert Shaw, is a salty World War II veteran. He has used his naval skills to open a shark-hunting business. He sells shark teeth, biding his time until he can make his next kill. In act two of the film, we learn why Quint has had a lifelong obsession with sharks. The audience realizes that Quint and the shark must fulfill their destinies if the town will ever be safe again.

Chief Brody is Ishmael, the everyman thrust into an otherworldly experience only to be the unlikely hero. He is the outside observer and the viewer sees the film from this point of view. His deadpan delivery of the ad-libbed “you’re gonna need a bigger boat” gets to the heart of simplicity of the audience’s collective terror. Like the narrator of Moby Dick, Roy Scheider is left clinging to the wreckage of the battered ship. Not accidentally, their small boat is named Orca, after the only creature in the sea known to kill sharks.

Richard Dreyfus most closely mirrors Queequeg, the seasoned traveler in search of new adventures. His character Hooper is like a storm chaser, travelling the world in search of the most intense and wild sharks. While his expertise leads him to the attacks in Amity, it becomes less relevant as the battle of wills overtakes any sort of zoological analysis. It requires the sacrifice of Quint, the expertise of Hooper, and the everyman ingenuity of Brody to defeat the shark.

It’s also important that the film is set in a New England seaside town. The Cape Cod-style fishing village mirrors the whaling town of Gloucester at the opening of Moby Dick. By setting the battle between man and beast in the location when Puritans landed, it also represents a quintessential American purity under attack — on July 4th, no less. There is nothing more American than going to the beach on a summer weekend. Loosing a maniacal beast on innocent revelers jeopardizes the very fabric of the audience’s perception of what is secure.

Spielberg tapped into the classic disaster movie trope by having the experts be ignored. Add to this mix a selfish, determined mayor who decides to open the beaches even though it isn’t safe. Brody, Hooper, and Quint try to convince the mayor that he will be risking the lives of the citizens, not to mention the long-term viability of the beachtown’s economy if people are killed. Brody in particular becomes Amity’s Cassandra, predicting doom when no one will listen, and having to watch your prediction come true. In this case, the audience knows the warnings are correct, thus ratcheting up the suspense as they wait for the next shark attack.

In the annals of summer blockbusters, only a few hold up decades later. Even fewer offer a genuine example of the era’s style while still finding something to say to a new generation. By referring to genre touchstones, Spielberg used a familiar foundation on which to build a genre-bending classic.

Originally written for DVD Netflix