By the time Alfred Hitchcock looked to adapt Robert Bloch’s novel Psycho, he was quite literally a household name. His most recent films at this point were an anti-Communist spy thriller, an artistically perfect romantic murder, and a transcontinental kidnapping plot. He had certainly never taken on anything like the slasher genre.

Even with his impressive resume and box office dependability, the studio was hesitant to greenlight a picture like Psycho. He trimmed and trimmed and trimmed until the budget was just over $800,000. He gave up his own salary for a 60% cut of earnings, and Janet Leigh—a massive star at the time—worked for a quarter of her usual rate for the chance to be in a Hitchcock film. These cuts, along with a brief shooting schedule, black-and-white film, and modest sets got the movie made.

And yet, for all that, Psycho is still more than a slasher film. Sixty plus years after its release, audiences are still jumping and cinema nerds like me are still noticing new things. Look beyond the superficial plot points for these very deliberate moments in Psycho.

*This post includes light spoilers*

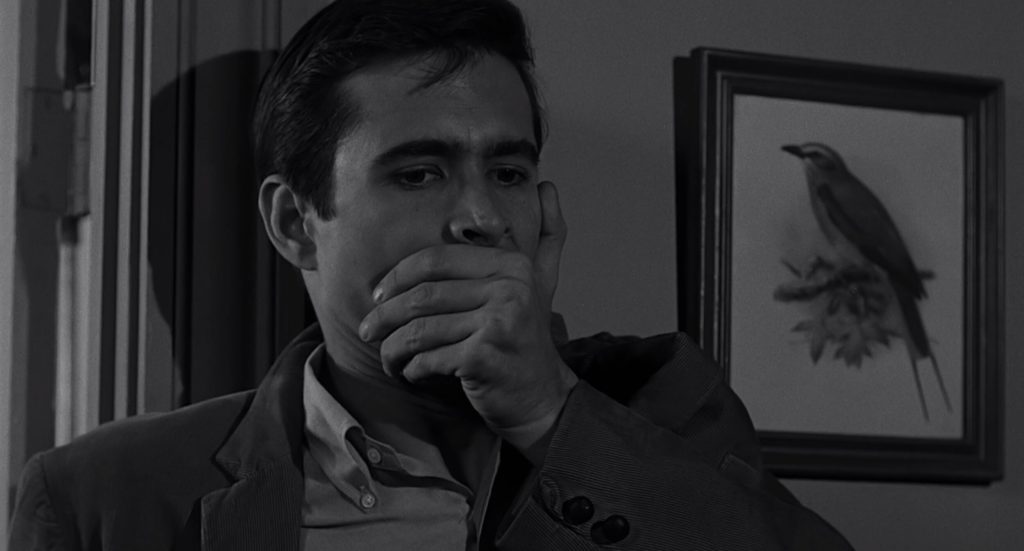

Bird Imagery

Birds were always a fascination for Hitchcock. I mean, he made an entire film about them. In Psycho, they are a bit more subtle.

Janet Leigh’s character is named Marion Crane, bringing up images of lithe, long-legged, stalking birds.

In the hotel’s office, Norman has decorated with a dozen taxidermied birds of prey. They are sharp-taloned, horribly-beaked, and posed in mid-attack. In life, they would silently swoop in and grab their prey, gone before they are noticed.

As stuffed birds, they perpetually exist on the edge of that moment, but never quite complete the task. Norman will cross that line.

All-strings score

Hitchcock partnered with Bernard Herrmann on several of his films. The composer always created individual themes characterized by rich orchestral arrangements. With Psycho, Herrmann decided to score the film using only strings. In addition to being a cost-saving measure, it was an unnerving style. And with Herrmann’s capable skill, the limited instrumentation was not a hindrance.

“Well, just as there’s tremendous range in black-and-white movies in the photography of them, Herrmann found tremendous range within this limited group of instruments, the string section. He made the strings extremely dry. He put mutes; he loved to have mutes on his strings. So it creates a very different sound from what we think of as the usual Hollywood romantic film score that used violins. It’s the exact opposite. It’s cold, it’s chilly, and he uses the strings also for percussive effects, since we don’t have the traditional things like timpani and all the sort of devices that film composers use to scare or startle people. He created percussive effects in the strings.” —Steven Smith, Bernard Herrmann biographer

Hitchcock originally wanted the famed shower scene to be without music — the only sounds being Janet Leigh’s scream and running water. Herrmann scored it anyway and put it in his back pocket. When Hitch was unhappy with the all-too-quiet murder, Herrman played the screeching accompaniment. It’s now so iconic that it’s hard to imagine the scene any other way.

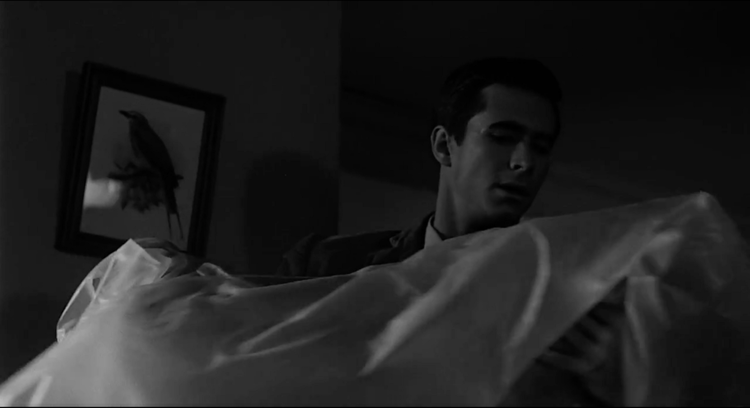

The money

At the outset, Janet Leigh steals $40,000 from her office before going on the run. A substantial amount of the film is spent following the cash. It may be the most dedicated Hitchcock is to one of his beloved MacGuffins. The audience sees Leigh every time she wraps the stacks of bills, or places them in a new handbag, or tries to hide them in her hotel room.

Upon first viewing, the audience is really pulled into believing the movie will be about Leigh and if she will get away with the money or will be caught. In fact, even as Norman cleans up his mother’s crime scene, the camera keeps the stack of cash in the foreground and in focus. Indeed, the audience becomes as concerned about whether or not Norman will discover the money as they are about his cleaning methods.

It’s Hitchcock’s genius that we’re halfway through the film before we realize it was never really about the money at all.

Flushing toilet

In today’s day and age, when it seems just about anything goes, it’s hard to believe things like a toilet were not only taboo, but downright forbidden to be shown on screen.

Launched in 1934, the Hays Code policed what could and could not appear in the movies. Everything from plot points to set dressing to hem lines was regulated by the code office. The long list included omitting any suggestion of toilets and bathrooms.

By 1960, certain changes had been made. This scene in Psycho was flagged by censors, but it was defended by Hitchcock and screenwriter Joseph Stefano. Stefano wrote stage directions of Leigh tearing up the paper and flushing it down the toilet so it would be deemed “integral” and could be included. Take that, censors.

Originally written for DVD Netflix