Julius Caesar did little more than land in southern England after conquering Gaul. He claimed British Isles for the Roman Empire and then left for more illustrious (read: warmer) locations. It wasn’t until Emperor Claudius returned in 43 AD that Rome really made an impact on the local landscape. In less than five decades, lower Britain was firmly within Roman control. And then the real building could begin. That included a coast-to-coast wall to protect Roman Britain from the attacks from the northern tribes (modern day Scotland).

Part of the Roman Empire’s success was its ability to scale up its trademark structures anywhere in the world. Long before Henry Ford’s assembly line, the Romans created standardized construction designs and practices. With little variation, they replicated everything — roads, toilets, forts, saunas, plumbing, and, yes, even walls.

In fact, they were so dedicated to their standard designs that they sometimes seem a bit silly in the real world application. There are a number of locations along the Wall that don’t seem like they needed defenses at all. There were even milecastle gates that open out over a cliff. They could have skipped building a gate that no one could possibly use, but the plans said they had to, so they did. Bureaucracy reigned.

When the Emperor Hadrian decreed a wall to be built on the northern edge of the empire, it took only five years for engineers to survey a route, terraform the landscape, and construct 70+ miles of fortified wall.

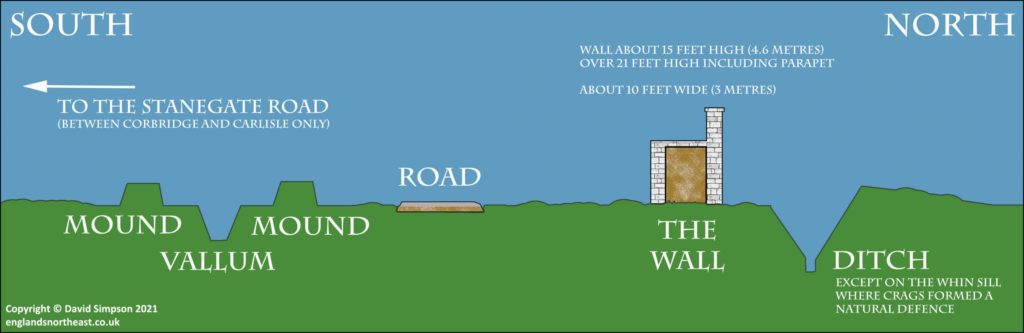

The wall was built out of quarried stones, chiselled into square shapes. The ‘outline’ of the wall was built, then the rubble filled the space inbetween. After that, wooden planks were erected, making the final wall somewhere about 9-10 feet tall, or even taller if there was a turret.

You have built a lengthy wall, made as if for permanent winter-quarters, in nearly as short a time as if it were built from turf which is cut in even pieces, easily carried and handled, and laid without difficulty. being naturally smooth and flat. You built with big, heavy, uneven stones that no one can carry, lift, or lay without their unevenness becoming evident. You dug a straight ditch through hard and rough gravel and scraped it smooth. Your work approved, you quickly entered camp, took your food and weapons, and followed the horse who had been sent out, hailing them with a great shout as they came back.”

~Emperor Hadrian, circa 128AD

Every mile was a milecastle, a small stone tower and gate to allow for passage of goods and travellers. Then, there were occasional strategically-placed turrets or mini-forts with some barracks or stables.

The Romans also erected places of worship on these windy moors. A Temple to Mithras, an ancient pagan cult, survives near Carrawbaugh. This one served the fort and supporting town of Brocolitia.

And then there were the legitimately massive forts, with a luxurious home for the centurion, working saunas and spas, granaries, stables, a hospital, kitchens and more. Plus, there were small towns and villages of Britons that sprung up around the milecastles and forts to support the soldiers.

All of this activity left behind evidence, and lots of excellent places for archaeologists to poke around. Housesteads lies just about at the halfway point and is often called the furthest edge of the Roman Frontier (although there were outposts in Scotland to the north). Housesteads is also home to the oldest extant toilet in Europe, so there’s that. Actually, while the people make jokes about it, the intelligent engineering is impressive. The water started flowing at the top of the hill, going through the kitchens, then the sauna, then the stables, before filling the pit under the outhouse. The outhouse was set at the lower edge of the slope, so the wastewater could be sent down the hill and away from the fort itself. It truly was much more advanced sanitary works than one would assume for the era.

Birdoswald is further west along the wall and has seen a number of functions over the centuries. Interestingly, it sits near the longest single extent of the wall, even though the first edition was turf. The further west the less available stone for building was. About five years after its first iteration, Birdoswald (and wall nearby) was refortified with stone, likely quarried further inland.

Even after the Romans left Britain in the 5th century, Birdoswald remained inhabited by various groups. Local chiefdoms, medieval monks, and middle ages lords were all in charge of the fortified area. The area was also a target for the Border Reivers, clans that raided opposing, or even unknown villages and castles.

Bastle houses had space for animals on the ground floor and accommodation above, acting as fortified farmhouses during the intense phase of raiding on the borders by the so-called ‘reivers’.

This house was occupied by the Tweddle family, who complained to the Warden of the West March on three known occasions, twice in 1588 and again in 1590, following raids from the reiving families of Elliot, Nixon and Armstrong, when large numbers of cattle were stolen. ~ English Heritage

In the Victorian era, the home was owned by a Roman history enthusiast who did a great deal of excavation and research, as well as amassed a huge collection of artefacts. Sadly, his son auctioned it all off as soon as he died. English Heritage assumed management of the site in 2004.

In 1987 the Wall was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site and in 2003 the official Hadrian’s Wall Path opened. Since then, thousands of people have walked end to end, like we did. Even more have visited portions of the wall or the forts to see the lasting impact that Romans had on the landscape and culture. I’m grateful to count myself among them.